The European Space Agency has secured five upcoming rocket launches to help regional companies test new satellites in orbit.

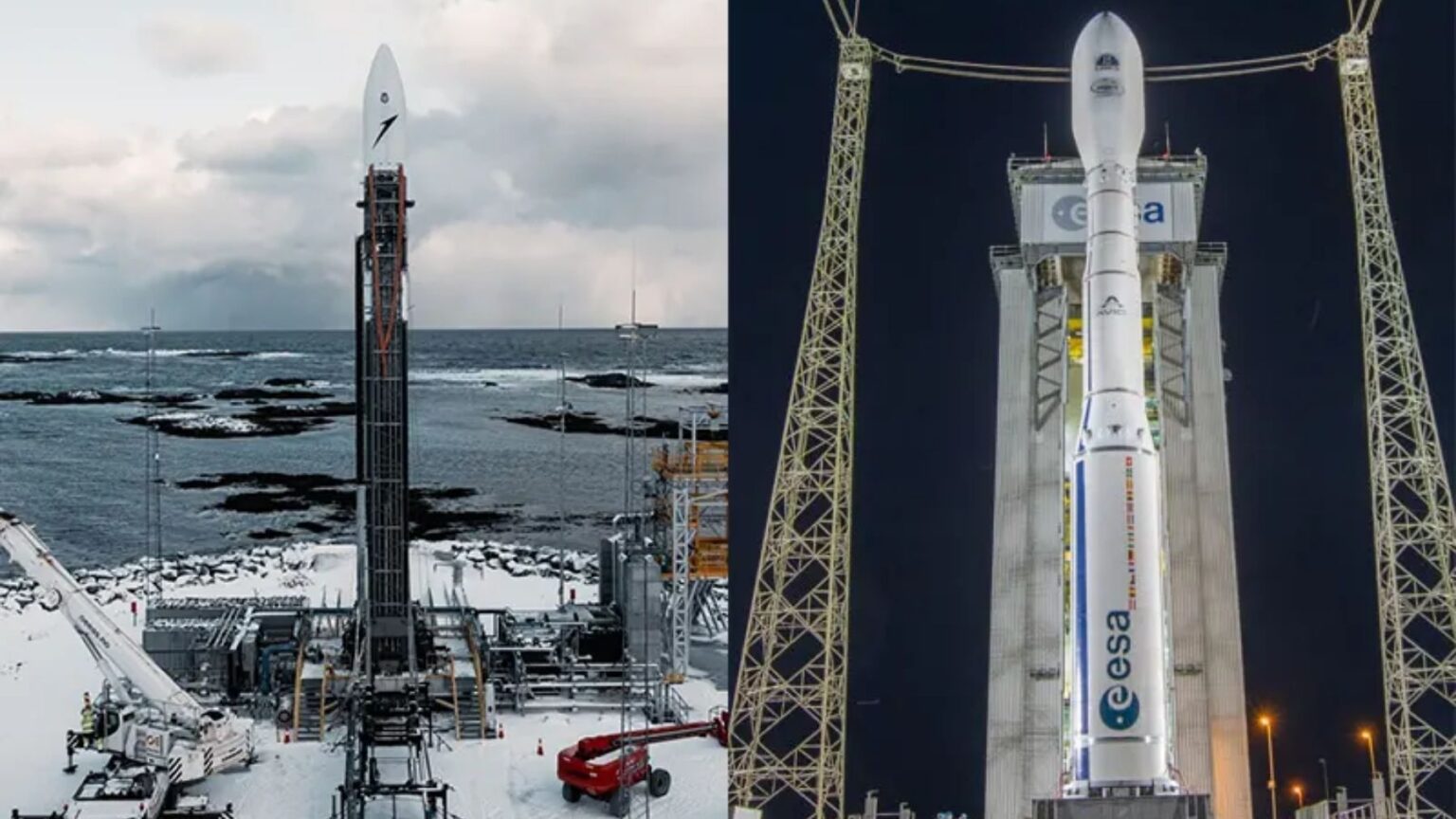

The agreements pair Italy-built rockets launching from South America with a new German rocket flying from northern Norway, expanding Europe’s options for sending small spacecraft into space.

Subsidized launch slots can turn a lab prototype into flight hardware, because vacuum and radiation expose weak designs quickly.

Oversight sits with a shared office inside the European Space Agency (ESA), which sets requirements for safety, timing, and payload readiness.

It’s Boost! program focuses on helping European launchers reach regular service, while sharing early risk with companies and governments.

How Europe funds space missions

A joint ESA and European Commission budget supports the Initiative, so new hardware can reach orbit before investors lose patience.

Each award can cover up to €5 million for launch and integration work, setting a funding ceiling.

Because providers compete for orders, the Initiative can spread opportunities across Europe while keeping procurement rules visible and testable.

Launch independence keeps schedules in European hands, which matters when climate sensors and security payloads sit on tight deadlines.

“These agreements demonstrate the trust European institutions have in our launch services,” said Isar Aerospace CEO Daniel Metzler.

New launch vehicles still must prove reliability, and a single failure can delay payloads while insurers and regulators review risk.

Riding along on Vega-C

Avio’s Vega-C missions often carry smaller spacecraft as add-ons, which lets new builders fly without buying a whole rocket.

ESA calls these auxiliary passengers, smaller payloads sharing a rocket ride, and the approach reduces cost but adds scheduling limits.

Because the main payload drives the countdown, secondary missions must accept late changes in timing and orbit selection.

A deployable tape tether can move electric charge through the thin charged gas around Earth, creating drag that lowers orbit over time.

The effect is called Lorentz drag, a braking force from current in magnetic fields, and researchers modeled it for the E.T.PACK project.

Tether braking works best in low Earth orbit, and it cannot raise altitude quickly when a mission needs emergency maneuvers.

Pluto+ packs power tightly

Small satellites often run out of power first, so engineers push flexible solar panels and efficient electronics into tight volumes.

DLR’s Pluto+ CubeSat, a satellite built from cube units, will test computers and a solar array that delivers 100 watts of power.

If the power system holds up, similar small platforms can run sharper sensors, but they still face short lifetimes.

GapMap-1 watches greenhouse gases

Tracking greenhouse gases from space depends on measuring how sunlight is absorbed, because each gas leaves a distinct pattern.

GapMap-1 will carry a short-wave infrared spectrometer, a sensor that splits light into narrow colors, tuned for greenhouse gas measurements.

Clouds, dust, and calibration drift can confuse those signals, so teams must validate results against ground measurements.

Spectrum adds new options

Dedicated small launchers can fly on shorter notice, because they do not wait for a larger primary customer.

Isar Aerospace will use its Spectrum rocket for two missions, including a debris cleanup rehearsal and a three-satellite CubeSat rideshare.

Because Spectrum remains new, each successful flight will matter, and early customers must plan for possible delays in debut years.

Tom and Jerry practice approach

Debris removal starts with close-proximity navigation, when one spacecraft matches another’s path and keeps a steady separation.

The Tom and Jerry mission will test rendezvous, controlled meeting of spacecraft in orbit, by flying a servicer within about 10 feet.

Without reliable sensors and software, the approach could fail or collide, so teams usually rehearse the same steps many times.

Cassini shares satellite space

Rideshare missions pack several experiments into one flight, which spreads cost and lets smaller teams test hardware in orbit.

For Cassini, Isispace will handle integration, fitting different payloads onto one spacecraft bus, and manage operations after deployment.

Shared missions demand careful power and radio planning, and one noisy payload can spoil data for the others.

What in-orbit tests prove

Ground labs can shake and heat a satellite, but only space can expose the full mix of vacuum, radiation, and sunlight.

That is why the Initiative funds an in-orbit demonstration, a test flight to prove hardware works in space, before scaling production.

A successful result still needs follow-up analysis, because one short mission cannot show how parts age across many years.

When rockets earn confidence

Launch services depend on long checklists, from propellant loading to range safety, and each item must pass inspection.

For new vehicles, engineers gather flight data on engines, guidance, and separation systems, then feed lessons back into design.

Even with subsidies, a thin launch market can strain factories and crews, so Europe needs steady demand, not one-offs.

Europe’s future in space

After each flight, teams downlink performance data and compare it with ground tests, looking for surprises and failures.

Clear evidence of success can unlock sales, because customers trust hardware that has survived launch loads and orbital conditions.

If the Initiative keeps booking regular flights, Europe’s small companies may spend less time fundraising and more time building.

Taken together, the missions show Europe paying for test flights that move ideas from benches to working satellites in orbit.

The next challenge is keeping those flights routine and safe, because independence only holds when launches stay frequent.

Image credit: Isar Aerospace / Simon Fischer / Wingmen Media / ESA / S. Corvaja

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–