Before jinn, before ghosts, before the word supernatural even existed, there was something much closer to humans.

The land itself was alive.

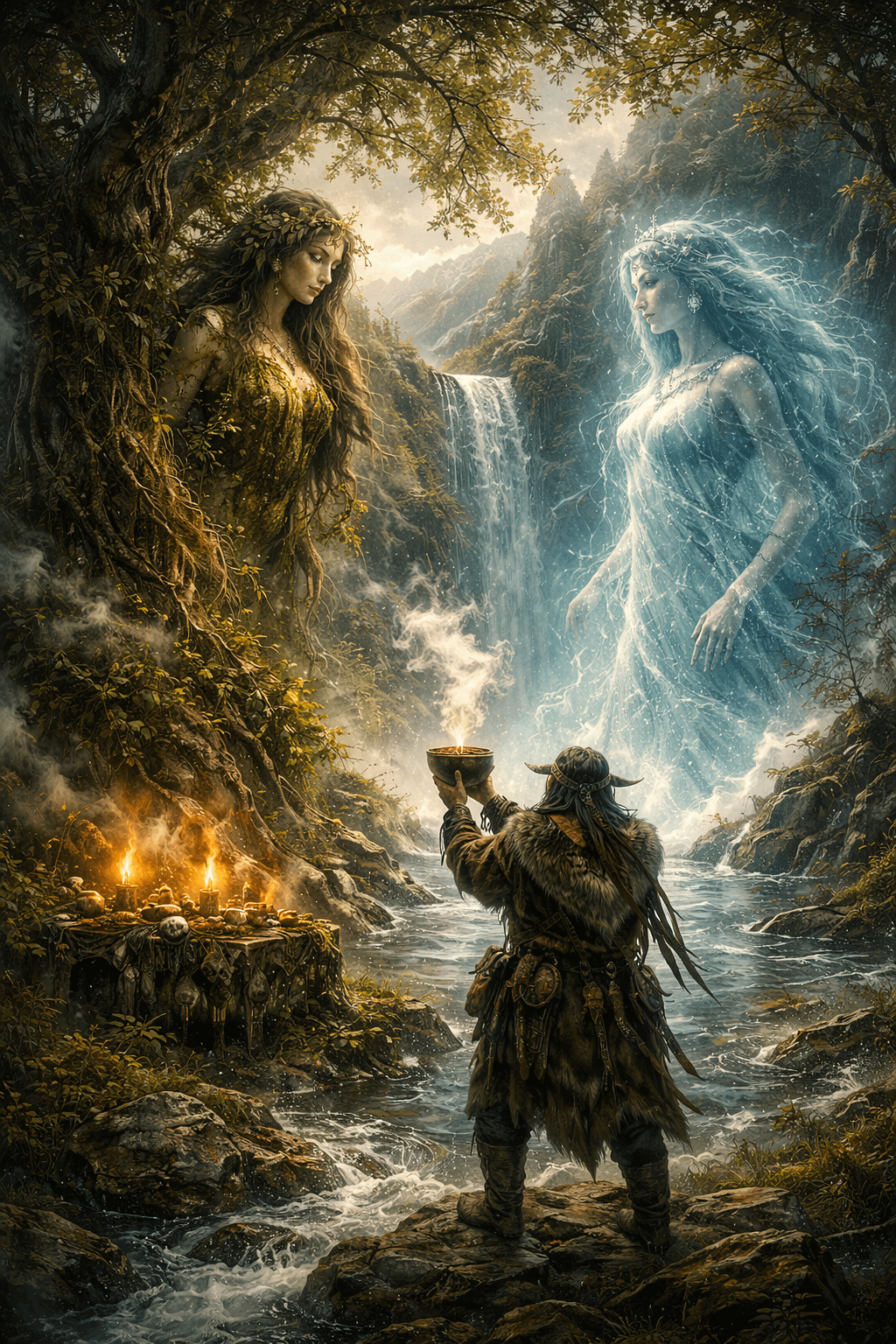

In ancient Turkic belief, nature was not just scenery. Mountains listened. Rivers remembered. Forests watched. This belief is known as Yer–Su — literally Earth and Water — but it goes far beyond those words.

Yer–Su were not gods.

They were spirits of place.

A mountain had one.

A lake had one.

A river bend, an old tree, even an entire homeland could have one.

And people knew better than to disrespect them.

Nature Was Never Silent

Old Turkic people believed that when you entered a forest, you lowered your voice.

You didn’t break branches for no reason.

You didn’t throw stones into water just for fun.

If you took something from nature, it meant the spirit allowed it.

Otherwise, something would go wrong.

Illness.

Bad luck.

Drought.

Loss of animals.

Not immediately — but inevitably.

Yer–Su spirits were thought to be closer to humans than sky gods. You didn’t need rituals or priests to offend them. A careless act was enough.

When the Land Punishes

There’s an old legend from the Göç (Migration) Epic.

The Turks, for political reasons, give away a sacred stone that had been protected by their ancestors for generations. Shortly after, everything collapses.

Birds stop singing.

Animals grow restless.

Plants wither.

Diseases spread.

Then people hear whispers from nature itself:

Only when the people abandon the land does the suffering stop.

The message is clear:

The land itself rejected them.

Spirits of the Forgotten Dead

One of the most unsettling parts of the Yer–Su belief is this:

Some Yer–Su spirits were believed to be forgotten ancestors.

As long as a person’s name was remembered, their spirit stayed close to the family.

But once forgotten, their soul merged with nature — becoming part of a tree, a rock, a spring.

So when people showed respect to nature, they weren’t just honoring spirits.

They were honoring their dead.

Sacred Waters That Heal — or Judge

Water held a special place.

Springs, rivers, hot baths — many were considered alive.

There are countless folk stories where a dying person follows an injured animal into a spring or mud pool and comes out healed after days.

People believed these waters had guardians — iyes — who chose who deserved healing.

This is why early Turkic people avoided washing their dirt directly into rivers.

Not out of ignorance.

Out of respect.

A World With an Axis

In shamanic belief, the world wasn’t flat or divided randomly.

There was a center.

A vertical line connecting:

- the underworld,

- the human world,

- and the sky.

This was called the axis of the earth.

Shamans traveled this path during trance — often through a sacred tree or pole placed in the center of the village. Not to worship it, but to move between realms.

Even the North Star was seen as a “sky gate” — a fixed point anchoring the heavens.

Why This Still Feels Familiar

If this sounds strangely modern, it should.

We still say:

- “This place feels heavy.”

- “That forest feels alive.”

- “That water is different.”

These are ancient instincts.

Long before jinn stories or ghost tales, people believed the world was watching back.

And maybe that belief never really left us.

by bortakci34