From meteorology, research to communication and navigation, many things in our modern lives would be far more difficult, if not impossible, without satellites.

But despite their importance to daily lives, they are, relatively, highly disposable. Currently they are single use only, being discarded when they run out of fuel or their equipment fails.

Article continues after video advertisement

Article continues after video advertisement

At that point, in an ideal scenario they should fall back to earth, burning up on re-entry, or in future recycled in orbit.

But that does not happen often as few of them are close enough to the planet and so they remain in orbit, adding to the so-called space-debris – tens of millions of objects larger than 1 millimetre, including leftover tools, fragments from collisions, rocket stages – circling around Earth.

Potentially, these are all dangerous. Orbiting at a speed of around 27,000 kilometres per hour, even an object 1 centimetre in size could cause incredible damage to anything else it hits.

Space agencies around the world understand the risks this debris poses to space missions. The European Space Agency (ESA), of which Slovakia is an associate member, has adopted a ‘Zero Debris’ approach, an initiative to reach ESA’s goal to significantly limit the production of debris in Earth and Lunar orbits by 2030 for all future missions, programmes and activities. This involves issuing recommendations and calling for innovations to tackle the issue, with an end goal to establish a circular economy in the form of in-orbit servicing, assembly, and even recycling.

And Slovakia may have something valuable to contribute.

Related article

Slovakia’s expanding ambitions in space

Read more

To stay up to date with what scientists in Slovakia or Slovak scientists around the world are doing, subscribe to the Slovak Science newsletter, which will be sent to readers free of charge four times a year.

Two areas of research

Understanding the scope of the problem – in low-Earth orbit, manoeuvring a satellite out of potential harm’s way is now commonplace, but requires costly fuel and for instruments to be turned off which loses data – the startup Space scAvengers was established in 2020 with two solutions in mind.

One involves in-house attachment technology that allows a robotic arms to capture a piece of debris. The other uses operational software based on multi-agent collaboration that allows a swarm of satellites to cooperate and communicate in order to capture and remove a piece of debris. For example, three satellites attach themselves to the piece, 9 more will gradually join them over the course of the mission, with two more observing and coordinating the effort.

“As a startup in the eastern part of Central Europe, we realised it wasn’t easy to break through in the space industry with something that involves space hardware development. What we lack is the developed investment potential, and, as a startup, relevant infrastructure,” Marek Gebura, one of the co-founders of Space scAvengers, told The Slovak Spectator.

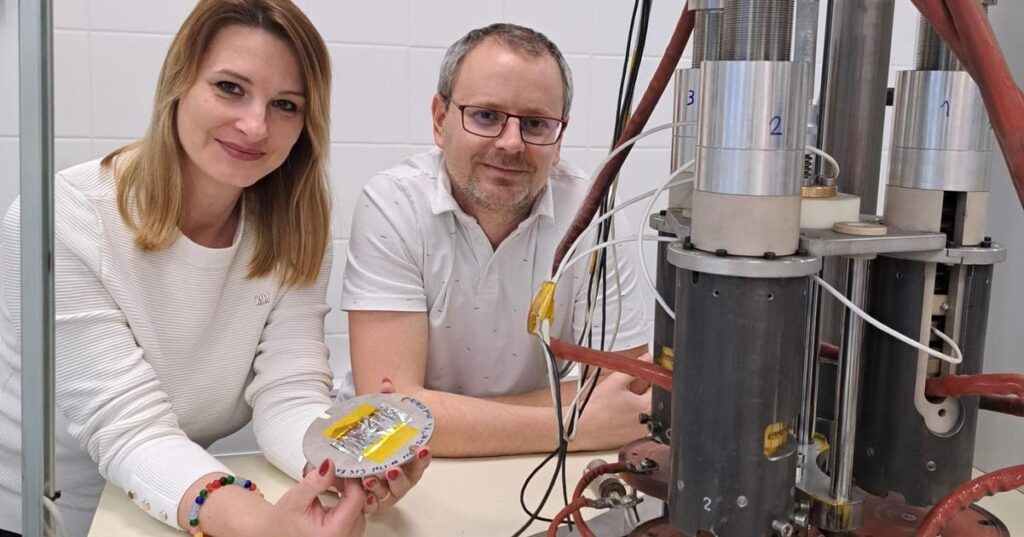

He added that instead of shelving the idea, the Institute of Materials and Machine Mechanics of the Slovak Academy of Sciences (IMSAS) stepped in and took over the research of the attachment technology. Gebura himself works at the institute.

This means the startup can now work on the other part of the project.

According to Naďa Beronská, the IMSAS director, the institute has a history of working on projects for ESA dating back to 2010. At the time, the institute was a partner in a consortium and working on understanding the effect of casting in space microgravity (a condition where the effects of gravity are very small). Later, as part of ESA’s PECS programme (intended to prepare countries for membership), the institute developed a magnesium-carbon fibre composite for structural parts of rocket bodies. Both partnerships yielded results, but the projects are waiting to move to the next phase of development.